Protecting your child from sexual abuse starts with information

By Cary and Tonja Rector

Few situations make parents feel more vulnerable than thinking about how to protect their children from sexual abuse and sexual assault.

As child and family therapists, the aftermath of sexual abuse and sexual assault is something we deal with regularly. Understanding an issue helps guide parenting decisions. One of the first steps to a better understanding of sexual abuse and sexual assault is to be clear about the realities. There are many misconceptions about sexual abuse, and media coverage can contribute to these misperceptions. Below are some facts about the issue and things for parents to think about and discuss with their children.

Researchers estimate that one in four girls and one in six boys will be sexually assaulted before age 18. In two-thirds of assault cases, someone known to the victim is the perpetrator; 38 percent of rapists are a friend or acquaintance. Forty-four percent of rape victims are children and teenagers. Sexual assault or abuse is far more common than most people would guess.

In order for abuse to occur there must be an inequity of power.Power can be in the form of authority, physical stature or age. Children are easy victims. They do not possess power and in our society are taught to respect adults and do as they ask.

Most sexual abuse involving children is not physically coercive. The more skilled the sexual perpetrator, the less physically coercive they are toward their victims. The majority of sexual abuse is perpetrated by someone the victim knows and sexual abuse of children most often takes place in the context of a relationship. The perpetrator is someone the child trusts. Sexual abuse betrays this trust. Children assume that people who care for them are not going to cause them harm or emotional upset. Young children don’t understand the betrayal until they are older and have a greater understanding of what happened to them. This betrayal of trust is one of the most troubling emotional and psychological aspects of abuse.

Sexual offenders are not a homogeneous group. They could be a single parent’s boyfriend, a coach, teacher, relative or older child. Often they appear perfectly normal and trustworthy. Realizing most sexual offenders do not fit a stereotype can help sharpen your awareness of situations that pose a potential risk. For example, boundaries regarding sleeping arrangements at family gatherings are often not considered when it comes to groups of children. Are kids of various ages, both boys and girls, all sleeping together in one room? Adults who are not married or in a relationship would not usually share a room, and the same boundaries can apply to children.

Sexual abuse always has an element of secrecy. Secrecy enables the offender to avoid consequences and maintain access to the victim. The offender manipulates the child in order to maintain secrecy and these manipulations can vary widely. The manipulations range from the child receiving privileges, gifts or adult attention, to threats of harm to a family member.

A child may be threatened that no one will believe her if she discloses the abuse, or she may be told she and not the perpetrator will be taken away from her family and punished. A child’s disclosure of sexual abuse, for this reason, should involve professionals who are able to help provide protection for the child. A sexual offender can become very desperate concerning the possibility of disclosure and may attempt to escalate his coercion to stop a child from disclosing the abuse. Rarely do sexual offenders accept responsibility for their actions. It is not uncommon for the offender to deny any involvement or to blame the victim.

Participation does not equal consent. Children are not able to give consent for sexual activity. Young children who experience sexual abuse may become more emotionally distraught as they become older and realize how much they were betrayed by someone they thought cared for them. The more closely related the offender is to the child, the greater the sense of betrayal and the greater the psychological impact.

Parents need to educate children about sex and sexuality. The public schools offer sex education programs; however, school programs’ content varies greatly. This is too important a topic to not participate in as a parent.

For young children, begin by identifying body parts and talk about private parts. Initially this may be uncomfortable for parents. There are many great children’s books on this topic you can read to help guide you. After talking about body parts and private parts, begin talking about good touch, bad touch and importantly, secret touching. There is no evidence that sexual knowledge leads to precocious sexual activity. In fact, the more accurate the knowledge your child has, the more power he possesses. This is not a one-time communication, but an ongoing process.

As children become older, talk about relationship issues. Discuss with adolescents the type of relationship they want before engaging in intimate sexual contact. Sex doesn’t prove anything about a relationship and sex can have adult consequences.

Talk about consent. Consent is based on choice and is possible only when there is equal power within a relationship. Giving consent is an active process, not a passive one. Adolescent girls can learn assertiveness and develop the ability to say “no.” Adolescent boys should hear about male responsibility, personal values and the elements of consent. Talk with adolescents about how to deal with someone who may pressure them for sex, how to handle someone who does not take “no” for an answer, feels sex is his right or uses emotional blackmail to obtain sex. Try to react to your adolescent’s disclosures in a way that encourages him or her to talk with you more in the future.

Educate yourself as a parent about childhood sexual abuse and assault. Then empower your children with knowledge concerning the subject. It may be an uncomfortable topic but information and facts are your best bet in trying to protect your children as they grow.

Books on Sexuality

A Very Touching Book … for Little People and for Big People, by Jan Hindman (AlexAndria Associates; 1983).

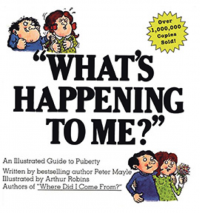

What’s Happening to Me? A Guide to Puberty, by Peter Mayle (Lyle Stuart Inc.; 2000)

Where Did I Come From?, by Peter Mayle (Lyle Stuart Inc.; 2000)

Your Body Belongs to You, by Cornelia Spelman (Albert Whitman & Co.; 1997)